Femoroacetabular impingement syndrome and labral injuries: grading the evidence on diagnosis and non-operative treatment—a statement paper commissioned by the Danish Society of Sports Physical Therapy (DSSF)

FREE

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2716-6567Lasse Ishøi1,

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4211-3516Mathias Fabricius Nielsen1,

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9856-7547Kasper Krommes1,

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2020-8792Rasmus Skov Husted2,3,

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2098-0272Per Hölmich1,

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3283-622XLisbeth Lund Pedersen4,

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9102-4515Kristian Thorborg1

Correspondence to Lasse Ishøi, Hvidovre Hospital, Sports Orthopaedic Research Center–Copenhagen (SORC-C), Arthroscopic Center, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Copenhagen University Hospital, Amager-Hvidovre, Denmark, Kobenhavn, Denmark; lasse.ishoei@regionh.dk

Abstract

This statement summarises and appraises the evidence on diagnostic tests and clinical information, and non-operative treatment of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) syndrome and labral injuries. We included studies based on the highest available level of evidence as judged by study design. We evaluated the certainty of evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation framework. We found 29 studies reporting 23 clinical tests and 14 different forms of clinical information, respectively. Restricted internal hip rotation in 0° hip flexion with or without pain was best to rule in FAI syndrome (low diagnostic effectiveness; low quality of evidence; interpretation of evidence: may increase post-test probability slightly), whereas no pain in Flexion Adduction Internal Rotation test or no restricted range of motion in Flexion Abduction External Rotation test compared with the unaffected side were best to rule out (very low to high diagnostic effectiveness; very low to moderate quality of evidence; interpretation of evidence: very uncertain, but may reduce post-test probability slightly). No forms of clinical information were found useful for diagnosis. For treatment of FAI syndrome, 14 randomised controlled trials were found. Prescribed physiotherapy, consisting of hip strengthening, hip joint manual therapy techniques, functional activity-specific retraining and education showed a small to medium effect size compared with a combination of passive modalities, stretching and advice (very low to low quality of evidence; interpretation of evidence: very uncertain, but may slightly improve outcomes). Prescribed physiotherapy was, however, inferior to hip arthroscopy (small effect size; moderate quality of evidence; interpretation of evidence: hip arthroscopy probably increases outcome slightly). For both domains, the overall quality of evidence ranged from very low to moderate indicating that future research on diagnosis and treatment may alter the conclusions from this review.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2021-104060

Statistics from Altmetric.com

See more details

Tweeted by 189

On 1 Facebook pages

28 readers on Mendeley

Introduction

Hip-related pain, typically affecting young and middle-aged individuals,1 2 is associated with reduced physical activity3 and poor quality of life.4 Based on imaging findings, hip-related pain is classified into (1) femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) syndrome, (2) acetabular dysplasia and/or hip instability and (3) cartilage and/or labral injury with normal bony morphology.5 FAI syndrome is the most common cause of hip-related pain,6 7 and is defined as a motion-related disorder of the hip joint caused by a collision between the head-neck junction of the femur with the acetabular rim due to cam and/or pincer morphology.1 This repetitive mechanical loading may result in acetabular labral8 and cartilage injuries.9–11

Consensus recommendations on diagnosis and treatment of patients with FAI syndrome/labral injuries have recently been published.1 5 12 While these have been guided by findings from systematic reviews,13–15 rating of the overall quality of evidence using a contemporary framework, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE),16 based on up-to-date risk of bias tools (risk of bias 2.0 for randomised controlled trial (RCT) studies and QUADAS-2 (A Revised Tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies) for diagnostic studies)17 18 is lacking. Since the GRADE level represents the confidence in the synthesised effect estimate, grading the evidence is the initial step towards developing clinical recommendations.16 To date, this has only been done for special tests concerning FAI syndrome,19 and for non-operative versus operative treatment20; however, the latter was not based on the risk of bias 2.0 tool.17 Furthermore, no summary of the utility of clinical information as a diagnostic tool is available. Consequently, this leaves general practitioners, sports physicians and physiotherapists—often the first healthcare professionals to see patients with hip and groin pain—with limited ability to judge the utility of diagnostic tests for labral injury,13 15 clinical information, such as self-reported symptoms for diagnosis,1 21 and the effect of different non-operative treatment strategies.14 To aid clinicians in the management of patients with FAI syndrome/labral injuries, this commissioned statement by the Danish Society of Sports Physical Therapy (DSSF) provides a systematic evaluation concerning the diagnostic effectiveness of clinical tests and information, and the effect of non-operative treatment strategies.

Methods

Authors

The authors were appointed by the DSSF and have different educational backgrounds (physiotherapists: LI, MN, KK, RH, KT, LLP; orthopaedic surgeon: PH; sports science: LI). LI, KT and PH have clinical and research expertise within the field of FAI syndrome through multiple scientific publications and daily treatment of patients non-operatively (LI and KT) and surgically (PH). KK, KT, RH and LLP hold expertise within systematic search of literature, LI, MN and KK have expertise within grading of the evidence, while LI, KK, MN, RH and LLP have expertise with risk of bias assessments.

Study design

This statement concerns two domains: (1) diagnosis, including diagnostic tests and clinical information and (2) non-operative treatment of FAI syndrome/labral injuries. To deal with heterogeneity in inclusion criteria and evolving terminology across studies, we included studies that involved diagnoses of FAI, FAI syndrome, acetabular labral injuries or a combination.5 In addition, we included studies with patients defined as having hip joint-related pain22 if this was not purely due to osteoarthritis, dysplasia and so on. We excluded treatment studies concerning only surgical interventions and/or therapeutic hip injections, as this statement was commissioned by the DSSF, and neither of these treatments are practiced by sports physical therapists in Denmark. For simplicity and to facilitate use of contemporary terminology,1 studies using the terminology ‘femoroacetabular impingement’ will be referred to as FAI syndrome. We employed two separate systematic searches to identify literature for each domain, with inclusion of studies based on the highest level of available evidence.23 Data were synthesised and the quality of evidence was evaluated using the GRADE framework.16

Literature search

Two systematic searches covering (1) diagnostic tests and clinical information and (2) treatment were conducted in Medline (via PubMed), CENTRAL and Embase (via Ovid) in July 2020 and updated in July 2021.24 No restrictions were applied concerning the year of publication, however, only publications in English were included. We searched individual text words in title and abstract supplemented with MeSH or Entry terms if available. For both domains we included the population of interest (eg, “Femoroacetabular impingement [MeSH]”) and combined this with test properties (eg, “sensitivity and specificity” [MeSH]) for the diagnosis domain, and with intervention (eg, “non-operative” OR “conservative”) and outcome (eg, “iHOT-33” OR “HAGOS”) for the treatment domain. In addition, reference lists of the included studies and relevant systematic reviews were scanned for potential references. A flow chart of searches (online supplemental file 1) and the complete search strategy (online supplemental file 2) as supplementary.

Supplemental material

[bjsports-2021-104060supp001.pdf]

Supplemental material

[bjsports-2021-104060supp002.pdf]

Selection of studies

Identified studies from databases were extracted to Endnote (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA) and automatically screened for duplicates. Subsequently, two authors (LI, MFN) performed a blinded screening of records to identify eligible studies. In line with a previous clinical statement paper,25 we included studies based on the highest level of available evidence.23 This means that we initially screened for systematic reviews/meta-analyses of diagnostic studies and individual studies on diagnostic effectiveness for the diagnosis domain, and for systematic reviews/meta-analyses of RCTs and individual RCTs for the treatment domain, as these represent the highest starting point for the GRADE assessment.16 If no systematic reviews/meta-analyses and/or RCTs were identified for treatment, we screened for observational studies. For the diagnosis domain, we aimed to include studies that compared clinical tests and/or clinical information, such as self-reported symptoms (ie, clicking, perceived restricted range of motion, etc) to either (1) diagnostic imaging, such as plain radiographs, MRI or arthrography (MRA) and CT, (2) intra-articular anaesthetic hip joint injection and/or (3) surgery. For the treatment domain, we aimed to include studies that compared different forms of non-operative treatment approaches or compared non-operative treatment against surgery on self-reported hip function. In studies evaluating the treatment effect using several self-reported measures of hip function, we report outcomes from recommended patient-reported outcome measures,1 26 such as the Copenhagen Hip And Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS)27 and International Hip Outcome Tool-33 (iHOT-33),28 if available, or we report other patient-reported outcome measures, preferably related to sports function, if available (eg, Hip Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS)-Sport Subscale).

Appraisal

Two authors independently assessed risk of bias (LI and MFN) of individual studies, as required for the GRADE framework29 and in line with Cochrane procedures. In case of discrepancy between raters, a third assessor (RSH) was included to facilitate agreement. We used the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias assessment tool (version 2.0) for RCT’s17 and QUADAS-2 tool for diagnostic studies.18 Furthermore, two authors independently assessed risk of bias (RSH and LLP) in systematic reviews using the ROBIS assessment tool.30 We chose risk of bias assessments rather than quality assessments in accordance with the Cochrane Collaboration, to reflect what extent the included studies should be believed as oppose to their methodological quality and reporting.31 If a systematic review/meta-analysis included a risk of bias assessment of individual studies using one of the assessment tools stated above, no further risk of bias assessment was conducted for these individual studies. However, if these tools were not used, we reassessed all risk of bias domains in the specific individual studies as part of this statement. This was the case for all studies included in the treatment domain.

Data synthesis

Two authors independently assessed the quality of evidence (LI and MFN) for each outcome related to diagnostic tests and clinical information (diagnostic effectiveness) and treatment (eg, hip function measured with iHOT-33) using the approach from the GRADE working group.16 Agreement was reached by consensus. The quality of evidence was graded as: (1) high certainty, indicating that further research is unlikely to change the confidence in the estimate of effect, (2) moderate certainty, indicating that further research is likely to have an important impact on confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate, (3) low certainty, indicating that further research is very likely to have an important impact on the confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate or (4) certainty very low, indicating high uncertainty about the estimate.16 For treatment purposes, the starting quality of evidence was rated as ‘high’ when data were based on RCTs.16 For diagnostic purposes, the starting quality of evidence was rated as high when based on cohort studies (prospective or cross-sectional).16 Subsequently, the quality of evidence could be downgraded one or two levels (eg, from high to moderate or low) for each of the following five domains of the GRADE approach: study limitations (ie, serious risk of bias such as lack of blinding of outcome assessor or other concerns determined to influence the study result),29 inconsistency (ie, the heterogeneity of the results across studies if more than one study was included for the specific outcome),32 indirectness (ie, poor generalisability of the findings to the target population, eg, uncertainty of the specific diagnosis due to inclusion criteria, use of a non-recommended patient-reported outcome measure, and/or uncertainty of the clinical value of a specific clinical test),33 imprecision of the estimates (ie, wide CIs)34and risk of publication bias.35

To facilitate informative and unbiased communications of the findings, the interpretation of the findings was based on the recommendations from the GRADE Working Group,36 which includes a set of standardised statements based on the combined effect size and grading.36

Diagnostic tests and clinical information

We used positive (LR+) and negative (LR−) likelihood ratios to assess the diagnostic effectiveness of clinical tests and clinical information in line with a previous statement paper25 and best practice recommendations.37 38 LRs express the change in probability of the patient having the diagnosis and/or injury.37 38 An LR+>1 increases the post-test probability of a diagnosis following a positive test, while an LR−<1 decreases the post-test probability of a diagnosis following a negative test. The diagnostic effectiveness of a positive and negative test was classified based on current guidelines as: very low (LR+: 1–2; LR−: 0.5–1), low (LR+: >2–5; LR−: 0.2–<0.5), moderate (LR+: >5–10; LR−: 0.1–<0.2); high (LR+: >10; LR−: <0.1).37 Diagnostic effectiveness of tests was downgraded due to imprecision of the estimates in cases where the 95% CIs of the LRs encompassed at least two categories of diagnostic effectiveness (eg, 95% CI ranging from very low to moderate diagnostic effectiveness in line with a previous statement paper.25

Treatment effect

We used standardised effect sizes (Hedges g) to determine the effect of treatment interventions in line with the Cochrane Collaboration.39 If this were not reported in included meta-analyses, we used Review Manager V.5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen) for the calculation to facilitate consistency of interpretation across studies.25 In such cases, we re-ran the analysis, if possible, using a random-effect model, unless otherwise stated in the original meta-analysis.40 Heterogeneity in study results was calculated using the I2 statistic, which is a measure to indicate the consistency of results across studies, from 0% (no inconsistency) to 100% (maximal inconsistency).41 For individual treatment studies not included in meta-analyses, we calculated Hedges g using a freely available Excel Sheet (Microsoft) applying between-group differences in change scores, if available, or else using between-group differences in follow-up scores.39 In both cases, Hedges g was calculated as an adjustment of Cohen’s d42using the correction factor .43 The magnitude of treatment effect across studies and meta-analyses were assessed as trivial (g<0.2), small (g≥0.2), medium (g≥0.5) and large (g≥0.8).42

Results

In total, 576 13–15 19 20 22 44–93 studies were identified. For a detailed overview of risk of bias assessments, GRADE, and which individual studies are contained in systematic reviews, we refer to online supplemental file 3.

Supplemental material

[bjsports-2021-104060supp003.pdf]

Domain 1: diagnostic tests and clinical information

For diagnostic tests and clinical information, we identified 6 systematic reviews13 15 19 84–86 and 26 observational studies6 44–68concerning diagnosis of FAI syndrome/labral injuries. One systematic review contained several meta-analyses of diagnostic effectiveness.13 The remaining systematic reviews did not provide additional information on diagnostic effectiveness above individual studies, and thus these were only used to retrieve risk of bias assessment if available. In total, we identified 23 clinical tests and 14 different forms of clinical information. Below we present only commonly used/studied diagnostic tests and tests with the best combined diagnostic effectiveness and quality of evidence (table 1). Diagnostic effectiveness of tests is presented within three categories: (1) FAI syndrome/labral injuries, (2) FAI syndrome and (3) labral injuries in accordance with reporting of the original literature. Clinical information was not found useful and is presented with a complete overview of diagnostic tests and their effectiveness in online supplemental file 4.

Supplemental material

[bjsports-2021-104060supp004.pdf]

Table 1

Diagnosis of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome/labral injury: effectiveness of clinical tests and grading the quality of evidence. ‘Quality of evidence’ refers to the overall quality of evidence for either positive or negative likelihood ratios across studies, whereas ‘diagnostic effectiveness across studies’ shows the range of diagnostic effectiveness (and number of patients) for studies of a specific test

Flexion Adduction Internal Rotation test

One systematic review and meta-analysis13 and 16 cohort studies45–52 56 60 61 63–65 67 68 were included to investigate the diagnostic effectiveness of the Flexion Adduction Internal Rotation (FADIR) test. For diagnosis of FAI syndrome/labral injuries, two meta-analyses reported in one systematic review13 using MRA56 63–65 (n=188) and surgery47 60 61 65 (n=319) as reference standard, and one additional study50 (n=49) observed a moderate to very low diagnostic effectiveness (LR+: 0.86–1.04 and LR−: 0.14–2.3; low to very low quality of evidence). For diagnosis of FAI syndrome, nine cohort studies45–49 51 52 63 67 (n=693) observed a high to very low diagnostic effectiveness (LR+: 1.00–3.30 and LR−: 0.09–0.83; low to very low quality of evidence). For diagnosis of isolated labral injuries, seven cohort studies49 56 60 61 64 65 68 (n=325) observed a high to very low diagnostic effectiveness (LR+: 1.00–2.30 and LR−: 0.06–0.76; very low quality of evidence).

Flexion Internal Rotation test

One systematic review and meta-analysis13 and four cohort studies6 45 55 66 were included to investigate the diagnostic effectiveness of the Flexion Internal Rotation (F-IR) test. For diagnosis of FAI syndrome, two cohort studies6 45 (n=304) observed a very low diagnostic effectiveness (LR+: 1.25–1.51 and LR−: 0.68–0.73; moderate quality of evidence). For diagnosis of labral injuries, one meta-analysis13 of two studies55 66 (n=27) and one additional study55 (n=30) observed a moderate to very low diagnostic effectiveness (LR+: 1.10–1.28 and LR−: 0.15–0.23; very low quality of evidence).

Flexion Abduction External Rotation test

Seven cohort studies44 45 50 52–54 56 were included to investigate the diagnostic effectiveness of the Flexion Abduction External Rotation (FABER) test. For diagnosis of FAI syndrome/labral injuries, three cohort studies44 50 53 (n=178) observed a very low diagnostic effectiveness (LR+: 0.73–1.10 and LR−: 0.72–2.20; low quality of evidence). For diagnosis of FAI syndrome, two cohort studies45 52 (n=138) observed a very low diagnostic effectiveness when using pain provocation as a positive test (LR+: 0.79–0.87 and LR−: 1.21–1.14; moderate quality of evidence), while two cohort studies52 54 (n=678) observed a low to very low diagnostic effectiveness when using restricted range of motion as a positive test (LR+: 1.01–1.36 and LR−: 0.41–0.93; moderate quality of evidence) (table 1). For diagnosis of labral injury, one cohort study56 (n=18) observed a very low diagnostic effectiveness (LR+: 1.70 and LR−: 0.78; very low quality of evidence).

Internal rotation in neutral hip position

One cohort study45 (n=63) observed a very low to low diagnostic effectiveness for prone internal rotation in neutral (0° hip flexion) hip position when using reduced range of motion as a positive test for diagnosing FAI syndrome (LR+: 4.83 and LR−: 0.76; low to moderate quality of evidence).

Domain 2: treatment

Eleven systematic reviews14 20 82 83 87–93 and 14 RCTs22 69–81 concerning treatment of FAI syndrome/labral injuries were identified. Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses compared different forms of non-operative treatment for FAI syndrome/labral injuries,14 90 and thus we included the most recent.14 In addition, seven systematic reviews and meta-analyses compared non-operative versus operative treatment20 82 83 87–89 92; however, since these were all based on the same three RCTs69–71 and thus provided almost identical results, we only included results from one meta-analysis.20 In addiction, one meta-analysis used inappropriate outcome measures and thus was not considered for inclusion.92 An overview of the content of the interventions is provided in table 2, while results are provided in table 3.

Table 2

Short summary of interventions delivered in the included randomised controlled trial studies

Table 3

Treatment of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome/labral injury: effect and grading the quality of evidence

Prescribed physiotherapy versus operative treatment

A systematic review and meta-analysis,20 based on three RCTs (n=574),69–71 showed a small effect and significant between-group difference on iHOT-33 at 8–12 months follow-up in favour of operative treatment for FAI syndrome (mean difference: 11.02 points, 95% CI 4.83 to 17.21, I2=43%, Hedges g=0.41) (moderate quality of evidence). Furthermore, one RCT (n=80) also reported on 24 months follow-up, observing a small and non-significant between-group difference on iHOT-33 in favour of operative treatment (mean difference: 6.3 points, 95% CI −6.1 to 18.7, Hedges g=0.23) (very low quality of evidence).70 For labral injury, one RCT (n=90) in adults above 40 years old showed a medium effect and significant between-group difference on iHOT-33 at 12 months follow-up in favour of operative treatment (mean difference: 12.11 points, 95% CI 3.27 to 20.96, Hedges g=0.61) (moderate quality of evidence).

Prescribed physiotherapy versus passive modalities, stretching and/or advice

A systematic review and meta-analysis,14 based on two RCTs (n=54),75 77 showed a medium effect and significant between-group difference on patient-reported function and pain (measured with iHOT-3375 and Non-Arthritic Hip Score; NAHS77) at 12 weeks follow-up in favour of prescribed physiotherapy for FAI syndrome (Hedges g=0.66, 95% CI 0.09 to 1.23, I2=0%) (low quality of evidence). Furthermore, an additional RCT (n=35) showed small effect and significant between-group difference on HOOS-sport at 6 weeks follow-up in favour of prescribed physiotherapy for hip joint pain (mean difference: 9.4 points, 95% CI 0.1 to 18.8, Hedges g=0.46) (very low quality of evidence).73

Comparison between different physiotherapy interventions

Three RCTs have compared different forms of physiotherapy interventions.22 72 74 Aoyama et al 74 (n=24) showed a large and significant between-group difference on iHOT-12 at 8-week follow-up in favour of hip and core exercises versus hip exercises alone for FAI syndrome (mean difference: 25 points, 95% CI 11.44 to 39.96, Hedges g=1.14) (very low quality of evidence). Harris-Hayes et al 22 (n=46) showed a trivial and non-significant between-group difference on HOOS-Sport at 12-week follow-up in favour of hip strengthening exercises versus movement pattern training for hip-related pain (mean difference: 3.69 points, 95% CI −4.36 to 11.74, Hedges g=0.19) (low quality of evidence). In addition, 12 months follow-up of the same cohort showed a medium and non-significant between-group difference in favour of movement pattern training (mean difference: 9.70 points, 95% CI −2.19 to 21, 59, Hedges g=0.59) (very low quality of evidence).80 Wright et al 72 (n=18) showed a large but non-significant between-group difference on HOS-Sport at 6-week follow-up in favour of hip exercises performed at home versus manual therapy and supervised physiotherapy for FAI syndrome (mean difference: 21.1 points, 95% CI −9.1 to 51.3, Hedges g=1.27) (very low quality of evidence).

Preoperative physiotherapy versus massage therapy

One RCT (n=18)79 showed a non-significant effect of 8-week pre-operative physiotherapy versus massage on self-reported function, measured with NAHS, at 12 weeks post-surgery (mean difference not reported; very low quality of evidence).

Prescribed postoperative physiotherapy versus advice

A systematic review and meta-analysis, based on two RCTs (n=47),76 78 performed by Kemp et al 14 showed a medium and significant between-group difference on iHOT-33 at 12–14 weeks follow-up in favour of prescribed postoperative physiotherapy for FAI syndrome78 and hip-related pain76 (mean difference: 14.37 points, 95% CI 2.98 to 25.77, I2=0%, Hedges g=0.67) (low quality of evidence). Furthermore, one RCT (n=28) also reported on 24 weeks follow-up, observing a small and non-significant between-group difference on iHOT-33 in favour of prescribed postoperative physiotherapy (mean difference: 7.1 points, 95% CI −5.5 to 19.6, Hedges g=0.38) (low quality of evidence).78

Discussion

In this statement paper, we have summarised the best available evidence and graded the quality of evidence concerning diagnosis (eg, special tests, self-reported symptoms, etc) and non-operative treatment for FAI syndrome/labral injuries. This statement paper extends on previous systematic reviews concerning diagnosis13 15 19 84–86 and treatment14 20 87–93 by providing an updated comprehensive overview of diagnostic effectiveness for both clinical tests and self-reported patient history characteristics. Additionally, we used contemporary risk of bias assessments (Risk of Bias version 2.0)17 of RCTs. Thus, this statement provides updated clinical guidance for clinicians working with hip and groin pain patients and, based on the grading of the certainty of evidence, a foundation for clinical recommendations.16 In summary, only a few diagnostic tests seem able to assist in ruling FAI syndrome/labral injury in or out, prescribed physiotherapy seems to be the most effective non-operative treatment for FAI syndrome; however, based on current evidence, is inferior to hip arthroscopy.

Diagnosis and clinical information

Diagnosis of FAI syndrome/labral injuries remains a clinical challenge,2 94 possibly due to extra-articular causes of groin pain having a similar clinical presentation.95 The Warwick Agreement defined FAI syndrome to be present based on a combination of symptoms (eg, stiffness, pain, etc), clinical signs (eg, positive impingement test, restricted range of motion, etc), and radiological findings (cam and/or pincer morphology).1 For clinicians without easy access to imaging modalities, knowing the diagnostic effectiveness of specific symptoms and clinical signs for FAI syndrome/labral injury is useful.

We found 23 clinical tests and 14 self-reported patient history characteristics (clinical information); many of which provided very limited utility in clinical practice when the goal is to accurately diagnose FAI syndrome/labral injuries. On its own, clinical information was not useful for the diagnosis of FAI syndrome/labral injury. The most useful clinical test for ruling in FAI syndrome was prone restricted internal hip rotation in 0° hip flexion (with knee in 90° flexion) with or without pain. However, due to the combination of low quality of evidence and low diagnostic effectiveness, the interpretation of a positive test is that it may only slightly improve post-test probability.36 Nonetheless, the test showed high specificity of 94%,45 indicating a low false-positive rate,96 and an LR+ of 4.83 associated with a potential clinically relevant shift in pretest to post-test probability from 51% (tertiary care setting)45 to 83% following a positive test. However, it should be noted that the pretest probability is considerably lower in primary care97 or sports setting,98 also lowering the post-test probability. Therefore, a positive test in a primary care or sport setting is probably not sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of FAI syndrome. Furthermore, restricted internal hip rotation was based on a subjective assessment making it prone to misinterpretation, which is also reflected by a weak level of agreement between testers (kappa value: 0.43).45 99 Finally, while the reference standard to label FAI syndrome in the study included combined groin pain, cam/pincer morphology and ≥50% pain reduction during an ultrasound-guided hip injection, and thus closely resemble the Warwick Agreement, the optimal cut-point or definition of pain reduction after an injection to define intra-articular hip pain is uncertain. However, while pain reduction >50% has been associated with cartilage injury100 which is often present in patients with FAI syndrome,9 this seems to be uncertain for labral injuries.50 100 These findings highlight the possibility that early-stage cases without cartilage injury but FAI syndrome may have been missed by the definition. The usefulness of restricted internal rotation for the diagnosis of FAI syndrome is partly in line with a Delphi study on diagnosis for FAI syndrome. Restricted internal rotation with pain (either with or without combined hip flexion) obtained consensus as a helpful component to include in the diagnostic process, whereas restricted internal rotation without pain did not.21

The tests with the best diagnostic effectiveness for ruling out FAI syndrome were no pain during FADIR and no restricted range of motion during FABER compared with the unaffected side. However, large heterogeneity in diagnostic effectiveness was observed between studies with negative LR− ranging from 0.09 to 0.83 (FADIR test) and 0.41–0.93 (FABER test), making the clinical application uncertain. Furthermore, the quality of evidence was rated very low for the FADIR test suggesting that the test may either increase/decrease/or have no effect on the post-test probability.36 The quality of evidence was rated moderate for the FABER test and combined with a trivial to small diagnostic effectiveness, this suggests that at best the test probably decreases post-test probability slightly.36 However, the restricted range of motion in the FABER test was determined as a longer distance between the lateral aspect of the knee and the examination table, and based on a comparison with the unaffected hip without cam or pincer morphology. This requires the unaffected hip to undergo radiological examination for the test to be valid, and thus the clinical implication is questionable.54 This is supported by a Delphi study that failed to reach consensus on the usefulness of FABER test for diagnosis of FAI syndrome.21 The FADIR test has recently been highlighted in the International Hip-related Pain Research Network consensus statement on diagnosis of hip-related pain as a useful test to rule out FAI syndrome5 due to the test being very sensitive.95 101 Since the test elicits high acetabular labral strains,102 and thus is expected to capture intra-articular pathology, no pain during the FADIR test is considered to rule out hip-related pain. Conversely, the test demonstrates poor specificity,95representing a high false-positive rate.96 Therefore, using the FADIR test as an isolated confirmatory test to diagnose FAI syndrome/labral injury or hip-related pain is not recommended.5 21

Few clinical and self-reported tests were useful for diagnosis of labral injury (‘clicking’, FADIR test and Third-test), however, all were deemed to be of very low quality of evidence. Thus the effect estimate can be interpreted as very uncertain, indicating these tests may either increase/decrease/or lead to no change in the post-test probability.36

An inherent limitation of most diagnostic studies is the use of hip arthroscopy and/or imaging as the reference standard to diagnose FAI syndrome and/or labral injury.13 Given the high prevalence of cam and/or pincer morphology103 and labral injury in asymptomatic cases,104 morphological variations and imaging or arthroscopic findings may not always be the cause of pain,100 105despite the labrum being densely populated by free nerve endings capable of transmitting nociception.106 107 Thus, the poor correlation seems to exist between hip joint morphology and pain100 108 and labral injury in symptomatic subjects undergoing hip arthroscopy is also poorly correlated to pain-relief after an intra-articular hip-joint anaesthetic injection.50 100

One of the cornerstones in diagnostic testing is to influence the choice of treatment approach and/or serve as a prognosis, with the aim of providing better outcomes for patients.37 All tests were downgraded due to indirectness.109 This is because it is currently unclear whether a specific diagnosis of hip-related pain5 actually changes prognosis and/or initial management strategy for patients, which in most cases comprises exercise-based interventions.12 110

Treatment

A recent consensus statement on treatment for FAI syndrome advocated a minimum of 12 weeks of physiotherapist-led treatment focusing on hip muscle strengthening and functional performance as the initial approach before surgery is considered.12 Our findings also support the use of 6–12 weeks of physiotherapist-led treatment (hip strengthening, manual therapy, functional training, movement pattern training) compared with passive modalities, stretching and/or advice (small to medium effect size).14However, these findings are associated with low to very low quality of evidence, suggesting that at best prescribed physiotherapy may improve outcomes. The large uncertainty is primarily driven by high risk of bias, wide CIs, and use of inappropriate patient-reported outcome measure (NAHS and HOOS-Sport)26 in three studies.73 77 80 Importantly, treatment outcomes after physiotherapist-led treatment may provide better results when patients are recruited through advertisements75 versus an orthopaedic practice,69 71 potentially reflecting patient bias regarding surgical treatment or differing disease severity status.

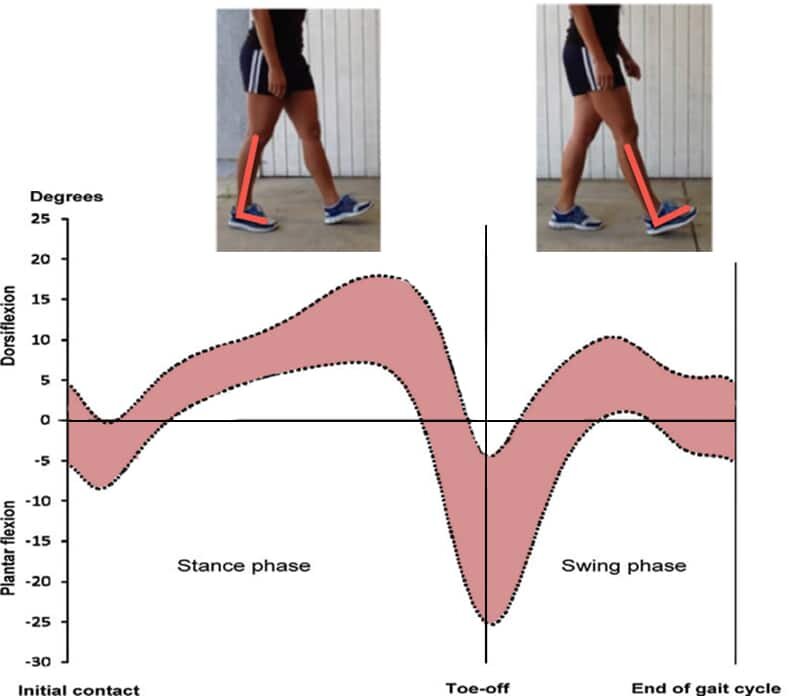

Three small RCTs with a 6–12 weeks follow-up compared different physiotherapy interventions. One study showed a large and significant effect of adding core exercises to a hip exercise programme, but the evidence is very uncertain due to the very low quality of evidence74; one study showed a large and non-significant effect of advice and home-based exercises versus manual therapy and supervised physiotherapy, but the evidence is very uncertain due to the very low level of evidence72; one study showed a trivial and non-significant difference between movement-pattern training and standard rehabilitation suggesting that the interventions may result in no difference (low level of evidence).22 However, 12-month follow-up suggests that within-group improvements are retained, indicating a potential long-term effect of non-operative treatment outcome.80 Due to the heterogeneity of physiotherapy interventions between these studies, it seems difficult to recommend a specific non-operative treatment approach (eg, movement pattern training vs hip strengthening) beyond exercise-based treatment.12 The mechanisms of improvements following exercise-based treatment are yet to be elucidated, but may be related to improvements in hip muscle strength14 and altered hip joint kinematics (ie, reduced hip adduction angle during single leg squatting)111 potentially reflecting better load-bearing capacity of the hip joint.112 113

In individuals eligible for surgery, a meta-analysis of three RCTs69–71 showed a small effect size in favour of hip arthroscopy for improving hip-related quality of life (iHOT-33) compared with prescribed physiotherapy at a follow-up of 8–12 months suggesting that hip arthroscopy probably improves iHOT-33 slightly more (moderate quality of evidence).20 However, the prescribed physiotherapy intervention was poorly described in all studies potentially limiting real-world implementation,69–71 and may not represent contemporary physiotherapist-led treatment.114 Noteworthy, the 95% CIs ranged from 4.83 to 17.21 points (iHOT-33), where the lower end does not exceed the minimal clinically important difference of 6 points,28 indicating that future studies may alter the conclusion. Prescribed postoperative physiotherapy including exercises and manual therapy versus advice showed a medium effect size for improving self-reported hip function after surgery for FAI syndrome and hip-pain indicating that this may increase postoperative outcomes (low quality of evidence).76 This is in line with a survey on postoperative practices among surgeons and physiotherapists, where >85% rated exercise therapy as ‘very important’ or ‘extremely important’.115

Although both operative treatment and prescribed physiotherapy are associated with improvements in self-reported function, many patients still report problems following both treatments, as indicated by the proportion not obtaining an acceptable symptom state following either surgery (50%)71 116 or prescribed physiotherapy (up to 63%–81%).71 72 This also seems to be the case regarding sports participation, with many athletes being unable to reach their preinjury level of sport and performance after treatment.3 117–121 Notably, 25% of physiotherapists and 50% of surgeons reported in a survey that they did not evaluate the readiness to sport after surgery and postoperative rehabilitation, which may leave many patients on their own in terms of managing the transition back to the sport.115

Methodological considerations

The current statement has potential methodological limitations. We decided a priori only to include RCTs on treatment, although prospective cohort studies on treatment outcomes of non-operative treatment for FAI/labral injury have been published.118 122–126 This was chosen since RCTs represent the highest starting point for the GRADE assessment,16 although low risk of bias cohort studies may yield an equal quality of evidence as a high risk of bias RCT. For a systematic review including cohort studies on treatment for hip pain, we refer to Kemp et al.14 In addition, we did not include treatment studies focusing solely on therapeutic hip injection, although we appreciate such modalities constitute non-operative treatment and is included in the Warwick Agreement as a treatment option. This was an a priori decision since sports physical therapists in Denmark are not allowed to practice injection therapy.1 Few studies have been published on therapeutic hip injections as non-operative treatment in FAI syndrome, showing small decrements in short-term hip pain (<2 months) and improvements in long-term (12 months) self-reported hip function; however, none of the studies included a control group.93 127 Since treatment studies normally use several outcome measures such as self-reported measures, muscle strength, biomechanical analyses, we decided a priori only to include data on self-reported measures. This was chosen in accordance with the GRADE framework, as patient-reported outcome measures represent patient-centred outcomes and thus contain the lowest risk of downgrading due to indirectness.33 The inclusion of three databases for the literature search (Medline, CENTRAL and Embase) may be perceived as a limitation. However, for musculoskeletal disorders these databases cover most literature, with a potential of missing only 2%,24 and is recommended by the Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews standards as the minimum databases to be covered.128 To increase the likelihood of identifying potential additional studies not covered by our literature search, we used alternative ways of identifying relevant literature such as checking reference lists of all systematic reviews identified.128

Conclusion

For diagnostic tests, restricted internal hip rotation in 0° hip flexion with or without pain was the best test to rule in FAI syndrome (low diagnostic effectiveness; low quality of evidence; interpretation of evidence: may increase post-test probability slightly), whereas no pain in FADIR test and no restricted range of motion in FABER test were best to rule out (very low to high diagnostic effectiveness; very low to moderate quality of evidence; interpretation of evidence: very uncertain, but may reduce post-test probability slightly). Clinical information such as self-reported symptoms was not useful for diagnosis. For treatment, prescribed physiotherapy consisting of hip strengthening, hip joint manual therapy techniques, functional activity-specific retraining and education showed a small to medium effect size compared with passive modalities, stretching and/or advice (very low to low quality of evidence; interpretation of evidence: very uncertain, but may slightly improve outcomes); however, prescribed physiotherapy was inferior to hip arthroscopy (small effect size; moderate quality of evidence; interpretation of evidence: hip arthroscopy probably improves outcomes slightly). For both domains, the overall quality of evidence ranged from very low to moderate. All treatment comparisons were associated with wide CIs, often crossing the line for minimal clinically important difference, indicating that future research on diagnosis and treatment may alter the conclusions from this review.

What is already known?

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) syndrome/labral injuries is a recognised cause of hip-related groin pain.

A comprehensive overview with grading of the quality of evidence related to diagnosis and non-operative treatment is lacking.

What are the new findings?

Restricted internal hip rotation in 0° hip flexion with or without pain was the best test to rule in FAI syndrome, however, the diagnostic effectiveness and quality of evidence was low, indicating high uncertainty in the estimate, and practically the assessment was prone to misinterpretation.

No pain in Flexion Adduction Internal Rotation test and no restricted range of motion in Flexion Abduction External Rotation test compared with the unaffected side were best to rule out FAI syndrome.

No forms of clinical information, such as self-reported pain location, clicking, locking, giving way were useful for diagnosis of FAI syndrome/labral injury.

Prescribed physiotherapy, consisting of hip strengthening, hip joint manual therapy techniques, functional activity-specific retraining, and education may be slightly superior to passive modalities, but are probably slightly inferior to hip arthroscopy.

Most outcomes were graded as very low to moderate quality of evidence with wide CIs, thus further high-quality research is likely to have an important impact on the confidence of these findings and recommendations.